I am currently conducting a (virtual) artist residency as part of the TAS programme, working alongside the TAS for Health project, that is exploring the potential for diagnostic interactive mirrors that could be placed in the home for people with conditions such as alzheimers, MS and strokes.

Background: The work I am conducting follows on from the Invisible Project that took place in 2017. This was an international collaboration between myself, researchers at MRL, Primary Studios (an arts centre) in Nottingham, and the British Brazilian artist Silvia Leal and the Flor de Pequi collective (an arts and community centre) at Guaimbê, in Pirenópolis (Brazil). The project resulted in the creation of several prototype performative interactive mirror experiences that were developed to connect the two places, across the UK and Brazil. We wrote a research paper about our findings from this research ‘in the wild’, focusing on the context and experience of interacting with the mirrors, outlining a series of design strategies for the future development of performative interactive mirror experiences [5].

See image above: Setting the Stage, Jacobs et al. (2019)

I have started this new residency by conducting a process of research and exploration, whilst getting to know more about the TAS for Health project and how the two projects might inform each other. My previous work with interactive mirrors had left me with several unanswered questions, that I have been taking time to explore.

Firstly, Why use an interactive mirror? Whilst my previous work focused on what we might do with an interactive mirror within a performance or theatrical context I felt I had never completely understood the mirror as an object, or technology, in its own right. Similar types of interactions can take place using interactive projections with a Kinect or a simple camera and facial recognition software, as I will explain later, and I couldn’t really understand how much the overlaying of a semi-transparent mirrored surface changed the interactive experience – beyond the ability to create additional performative spaces around the mirror (as shown by our diagram above, for setting the stage with an interactive mirror). Even with our findings on the space in front of, within and behind the mirror I felt there was not that much new for my artistic practice that hadn’t been previously explored through previous research into presence, projection and performance by artists and researchers such as Paul Sermon [8], Janet Cardiff [6], Johannes Birringer [7] and Gabriella Gianacchi [4].

Telematic Dreaming, Paul Sermon 1992

Secondly, in response to the TAS for Health project I have become very interested in exploring whether interactive mirror experiences can become a meaningful and trustworthy addition to people’s lives? Specifically in response to the now well known concerns around the built in biases in the facial recognition software often used in interactive mirror experiences, and the inability for tracking software such as the Kinect to detect different bodies, mobility and movement, skin colour, hair and body shape.

These concerns have led me to go right back to the beginning of the history of mirrors and explore a series of questions:

What is unique, attractive and novel about the mirror object on its own terms?

How have different people and cultures around the world traditionally interacted with mirrors?

How does the analogue technology of a mirror make this different from other technologies (e.g a phone, a camera, a screen)?

What happens when we layer data capture and interactivity onto each of these existing ‘analogue’ technologies?

How does this make the interactions different – and therefore the trustworthiness of these interactions?

Finally, through a parallel artistic practice-led process I am hoping to explore how the physical, conceptual and material context of the mirror disrupts or gains our trust in what is reflected and how this impacts on our sense of self, through our interactions with our ‘mirror self’.

You Talking to Me?

When we look directly in the mirror we see ourselves. What happens when the reflection of ourselves is disrupted… and we discover someone else is watching?

In 1967 Guy deBord described society as increasingly a spectacle of the self [3].

In 2002 the documentary film maker Adam Curtis created a series called ‘The Century of the Self’ [2] expanding on DeBord’s concept to suggest that twentieth century culture encouraged a belief in self actualisation that created new ways for governments and corporations to maintain political and economic control, through the emphasis of our individual desires over our personal and collective needs.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/p00ghx6g/the-century-of-the-self

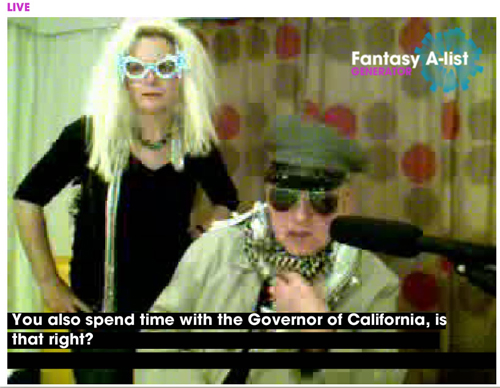

In 2008/2009 my artist collective Active Ingredient developed two interactive installations – The Fantasy A-List Generator and You Talkin’ To Me? These works responded to this hypothesis, as we also witnessed an increasing obsession with selfies and celebrity culture.

The Fantasy A-List Generator, Active Ingredient, 2008

In each installation a small photo booth was set up, one in an art gallery and one in the reception area of a media centre. Once inside people could sit on a seat facing a screen that acted as a mirror. The person’s image captured by a camera above the screen was embedded within an interface that played out once the participant pressed a button next to the screen.

In the first installation people started by choosing a celebrity name. They were then invited to dress up as this celebrity character, using the clothes on a rail that was placed within the booth. When they were ready they pressed the button. In this case the interface was designed to look like a TV interview, with the interviewee’s name appearing on the screen and a series of questions appearing in a ticker below their image. The questions were taken from real TV interviews with the celebrity. In this case the participant was invited to respond with their own answers. A timer appeared giving them a countdown to limit the time they had to answer each question. Once recorded the video was projected onto a large screen outside the video booth, in the public gallery, and was added to an online database that could be viewed via the project website.

In the second installation the screen was made to look like a distorted mirror, the video camera capturing the image had a fish eye lens and the mirror was high up so the person had to look up into the mirror. Again the participant was invited to dress up. In this case the question ‘you lookin’ at me?’ was posed, to encourage people to talk directly to the person they encountered in the mirror – that was at once themselves but not themselves.

Both artworks played with the concept of the ‘accurate reflection’ in the mirror, how a mirror not only reflects our image but also our sense of identity, disrupting the distinction between our private and public/performative selves. In both cases people were asked to enter the booth on their own or in small groups, creating a totally private space, the interface only reflected the person/people in the booth.

In both installations people appeared to forget that the videos would be made public. All kinds of people entered the booth; old ladies with their shopping bags; parents and their children; we even discovered the security guards at the gallery had done secret recordings after the gallery was closed. They dressed up and spoke to the mirror, seeming to lose their inhibitions once the door was shut and their costume was on. Creating a form of confessional.

The first installation allowed people to imagine themselves into a purely performative sense of self, taking on the character of another ‘famous’ person to become a member of society’s ‘A-List’.

The second installation played with the idea of losing yourself so much that you disassociate from your own reflection. This is a classic trope used by film directors to indicate a protagonists descent into madness. We based this second installation on the scene in Taxi Driver [9] when the character Travis Bickle (played by Robert De Nero) threatens himself with a gun in the mirror and asks himself ‘You talkin’ to me?’

We were also influenced by the film Donnie Darko [10], where the teenage Donnie sees Frank the terrifying rabbit in the mirror. In this case both the reflection and the surface of the bathroom mirror lose their trustworthiness. Donnie is able to create ripples on its surface with his hands and Frank responds in the same way. Similarly in the installation by using a fish eye lens and raising the mirror, we changed the sense of an accurate reflection.

This cinematic trope leads us back to the historical vision of a reflective surface as a portal to another world – the mirror in Alice Through the Looking Glass – and the potential for the occluded mirror to reveal that which we cannot see.

These two works explored both the positive and negative possibilities for an accurately reflective surface that hides an invisible presence or audience, as well as encouraging us to capture and reveal something that is hidden or unexpected within ourselves, below the surface of the spectacle of the self.